The myth of an apolitical science

The absence of the absence of evidence

Over the summer, one of the most politically-charged anti-trans documents ever generated by a world government was released by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, under Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Like a cardboard cutout of the Cass Review with more brazenly anti-trans rhetorical framing [1], it parroted several lines about scientific evidence which while deeply specious, were nevertheless foundational for the Supreme Court’s inevitable but devastating ruling against trans rights in United States v. Skrmetti.

When Justice Thomas writes in his concurrence “This absence of evidence is a “major drawback” in assessing the effects of puberty blockers on children with gender dysphoria” he collapses a complex, very real evidence-base into non-existence through what I can only describe as rhetorical magic. Because there is plenty of evidence, and even Thomas admits later that there are actually a host of uses for gonadatropin medications for which they are FDA-approved (endometriosis, prostate cancer, pre-menopausal breast cancer) all after rigorous study and robust clinical trials. Indeed, they’ve been used for 40 years to treat Central Precocious Puberty — for which they are also FDA-approved.

In this light, Thomas’ qualifier of “for gender dysphoria” is not a formality, but rather an admission that evidence on safety does indeed exist, if not always for the uses claimed, but for other young people whose bodies are not magically different because they are presumptively cisgender. But while there is an element of truth to the claim that there is more data to be collected, there is far, far more than the Trump (or Starmer/Streeting, for that matter) administration wants you to believe. A search for “GnRHa”, short for gonadatropin-releasing hormone agonists/antagonists on PubMed shows 3,293 results. There are more articles with the word “transgender” on PubMed than “ivermectin.”

What they mean is that there isn’t evidence they will accept, or which meets an evidentiary threshold inappropriate for the research question. But that doesn’t mean better data wasn’t incoming. Predictably, these studies were recently cancelled by the Trump administration. No clinician nor scientist I have ever met objects to the continued rigorous application of the scientific method to advance human health. It's just that this is not the same as saying there is no evidence. It is not, even, to say that the data that exists is wrong.

Gender-affirming care, is not, however, the only area of medicine for which HHS is creating these dubious reviews. Several vaccines are now under review, as are food additives. Famously, Secretary Kennedy claimed after his confirmation he would identify the “causes of Autism” by September. When September came, Secretary Kennedy pointed the blame at an unexpected party: Kenvue, the makers of Tylenol, the brand name for the generic drug acetomenophin/paracetamol. This bizarre episode has now expanded into a lawsuit by the Attorney General of Texas against Kenvue in late October. On November 14, a judge denied Paxton’s request to block shareholder payments while the suit goes forward. The genesis of the HHS claim can be found in a systematic review published only a month prior in August in Environmental Health.

HHS has also set its sights on a traditional conservative target: abortion and contraception. Kennedy has ordered a review into mifeprestone, a drug so fiercely contested by conservatives that the fight has already made it to the Supreme Court. As reported by Huffpost, Minnesota Senator Steve Daines greeted this news by tweeting: “The science is clear: the abortion pill is not safe for women.”

The horrifying ramifications of the impending review aside, this rhetorical shift is an odd one. “The science is clear” has long been a liberal catch-phrase used to oppose everything from conversion therapy to abortion restrictions, and central to messaging around climate change and vaccines. Where for decades the right has trafficked in uncertainty around science, the new right now believes it can speak for science. This should worry all of us greatly.

Save perhaps for theology, there has possibly in history never been a topic as rife for political abuse as science. It’s not an accident they’re both frequently mistaken for one another. This is maybe most true throughout the history of medicine. But the “politicization of science” – a phrasing which seems to erroneously suggest that science has ever existed as an apolitical force independent of powerful interests, has become a core phrasing of the modern right-wing in its war on three groups of people: gay people, transgender people, and anyone with a uterus – especially anyone who has the misfortune of being transgender, gay and having a uterus in the most evangelical iteration of the United States since the beginning of the Cold War.

What we might call the modern anti-science movement, starting with efforts to hide the obvious linkage between tobacco and cancer, and the rise of “climate skepticism”, has grown in scale enormously in the past half century. With the cross-pollination of dollars from the fossil fuel industry, the anti-abortion right and the war on trans youth, a politically motivated and morally bankrupt industry of experts-for-hire has been generating counter arguments for legal battles at unprecedented rates.

But if the alleged “politicization of science” were a new thing, Galileo would have seen more than his living room after 1632, and it would have taken us easily a hundred fewer years to accept germ theory as the dominant theory of infectious disease. It’s also likely that somewhere in the neighborhood of a hundred million fewer people would have died prematurely from tobacco-related cancers over the past fifty years. That number may actually be low. Science has always been an ideological battleground.

The question of quality

Science has always had to contend with two enormous problems it has yet to remedy: the difficulty in describing and quantifying phenomena, and the difficulty in deciding how to interpret and analyze the things thus described. “Happiness”, for example, does not lend itself to easy measurement because it is not a thing that can exist without context. This is a risky thing to say as a mental health professional, but I suspect that anyone who attempts to describe the state of happiness without using qualifying terms or context would struggle to create a definition materially different from how most people describe morphine.

Does this mean that our definitions of happiness which also might describe narcotic euphoria are wrong? Not necessarily. To suggest that you would have to reject the possibility that someone with a painful illness who receives adequate pain management can ever be happy. Or, more precisely, that anyone who achieves such a state after adequate pain management be precluded from using that term to describe their experience. This feels shortsighted, if not bleakly ableist. This may be why, when we focus on illnesses like measles — which is making a comeback thanks to the current “just asking questions” approach to vaccines — opponents of mass vaccination point to the death rate. Three in 1,000 people, they argue, is a small direct mortality rate (no, it isn’t) for something from which most people, upon recovering, are immune more or less for life. But aside from blindness and other horrendous long-term effects of the virus, the lifetime immunity talking point glosses over immune amnesia, which means that after someone recovers from the virus, they are susceptible to a vast array of other pathogens to which they were previously immune.

How we measure things, and what variables we cluster together to qualify those measurements, is a deliberative choice. As is the question of what methodology to use to test a research question. As is, if we want to put a finer point on it, the choice to decide at what point we have failed to reject the null hypothesis (see: alpha).

In efforts to control for bias, the rise of “Evidence Based Medicine” (EBM) has proposed that there must be some sort of objective process for sifting through the burgeoning ranks of scientific literature. On its face it is a laudable goal, but the limitations of the methods which have been developed thus far come loudly into the sphere of public policy with deeply concerning results. When Princeton political scientists Stephen Macedo and Francis Lee claim in their bestselling postmortem on COVID-19 policies that “the evidence supporting non-pharmaceutical interventions” such as masking and school closures for controlling the spread of the pandemic was “very poor”, they make several critical mistakes even while appropriately applying the language of EBM.

Under the GRADE Standard, the “highest quality” of evidence is a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), with lower quality ratings assigned based on various aspects of methodology. What it doesn’t do, is rerun the data or rerun the experiments themselves. GRADE cannot tell you whether the results or conclusions were incorrect, it can only approximate a grade of certainty relative to the conclusions, and whether there was high or low potential for bias. In other words, what Macedo and Lee actually mean as Michael Hobbes and Peter Shamshiri discuss in If Books Could Kill, is that there aren’t RCTs evaluating many of the interventions chosen because many of the interventions upon which we relied to respond to the largest pandemic since the Spanish Flu were based on studies conducted under less-than-ideal laboratory conditions. This tells you nothing about whether or not the interventions work.[3]

But this itself presumes that the same study design is ideal to evaluate enormously different questions. In actuality, the field of research methodology is complex. Even before ethical dilemmas are introduced (such as the ethical problems with randomly assigning some children to go to school to see who gets sick in order to establish whether school closures are effective mitigation strategies – something we should all agree would be a literal crime against children), we have to contend with the difficulty posed by constraining factors inherent to the problem being studied.

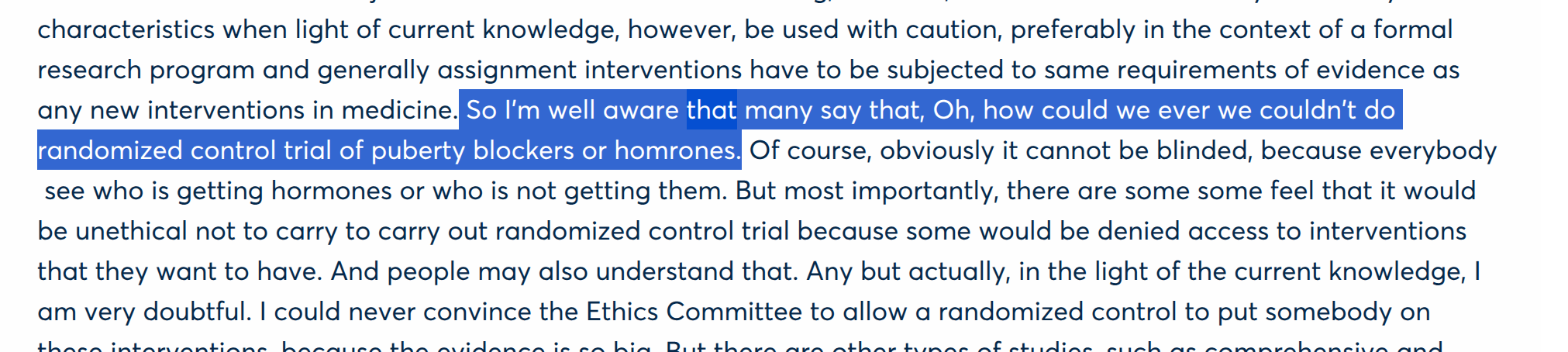

Detractors of gender medicine actually know this. In June 2024, Finnish psychiatrist and Cass Review advisor Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala had this to say to an audience in Paris of a joint conference between the Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) and psychoanalytic outfit Observatoire la Petite Sirène (apologies for the slightly garbled Otter.ai transcript):

“...in the light of the current knowledge, I am very doubtful, I could never convince the Ethics Committee to allow a randomized control to put somebody on these interventions, because the evidence is so big.”

At the end of the day, most scientists agree that an RCT is not an appropriate methology for evaluating most of GAC at this point.[2] And this is where GRADE, and systems similar to GRADE, falter. While it’s true that we should always reach for the most rigorous possible study design, it has also never been the standard that scientists should reject evidence if a better form of evidence is theoretically possible. Nor when the science in question is pursued in medicine does it mean that we withhold treatment when compelling observational evidence exists to suggest we have the potential to ameliorate significant suffering. While the EBM movement has indeed contributed greatly to the push for better quality evidence and ever more rigorous standards for research, it has also created a plausible mechanism for opponents of scientific progress to discount enormous volumes of data using scientific language and ritual as a costume.

Systematic reviews attempt to resolve this quandary by looking at multiple studies at once. To control for researcher bias seeping into ratings, they require researchers to evaluate each item of evidence according to a scale. The scale is created ahead of time, and looks at items like the presence of a control group or the inclusion of relevant covariates in statistical analyses. But this, too, requires a degree of precision on the part of the scale developer, and ultimately requires researchers to make judgement calls about which covariates are essential, and which are okay to leave on the cutting room floor

When the York team behind the Cass Review decided to exclude studies which contained mixed (eg, minor and non-minor) ages which were not clearly delineated by minority/majority status, this allowed the study team to exclude an enormous amount of data. This is varyingly true of many of the items on the modified Newcastle-Ottowa Scale they used: what constitutes a point deducted or a point reduced is a judgement call. The difference between this and what we typically mean by “study bias” is that the judgement call is made before the data is evaluated. It is a judgement call nevertheless. The reader, without doing the analysis over, cannot deduce from the results of such a process alone what might have been different with slightly different items.

This is most obvious when looking at the actual HHS report, which is itself not a systematic review, but a level of further abstraction away from the original data called an “umbrella review”. The same studies, when reviewed as part of other systematic review processes were rated differently. A systematic review published only a few weeks after the HHS report states, after looking at the available evidence on puberty blockers that “of the 51 studies, 22 were rated as moderate to high-quality evidence.” But how can this be when the York team so recently stated that no high quality evidence exists? The answer, like most of science, is that there isn’t some magic formula.

Three months after the systematic review which led to the bizarre anti-Tylenol presser, another systematic review was published, this time in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

“Acetaminophen use during pregnancy was not associated with the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) when considering physician-based diagnoses. No significant increase in the risk of other NDDs was observed.”

The more than two dozen scientists involved in this review conducted a different type of analysis in addition to the systematic review. A meta-analysis pools results from previous studies to allow scientists to run statistical tests on the evidence base as a whole. While it doesn’t re-run the original data, and therefore is limited by the methods of the accumulated studies, the strength of a meta-analysis is that it combines the total sample and adjusts for the error rates reported by previous authors. The authors of that meta-analysis review did not reach the same conclusion as the previous team. Then just this month, a second review found the same lack of association between Autism and acetaminophen. As far as I can tell, neither review has been the subject of any significant news coverage, although the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) provides this explainer.

The author of the HHS-lauded review concluded with a word of caution that patients should follow the directions of their physicians. As the authors note, as much as it is an imperfect drug Tylenol is used to treat pain and fever, both of which can impact a developing fetus. Fever alone can cause misarriage, and the antipyretic nature of the drug may call into question whether fever itself is a confounder — a variable which makes interpreting statistical analysis difficult by either obscuring relationships or making one appear to exist where it does note. Autism and ADHD may have been the outcomes of interest in the aforementioned reviews, but they’re not the only conditions of relevance. All authors agreed that clinical judgement should prevail when it comes to individual care. The American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (ACOG) advises that they continue to advise that Tylenol is safe and effective during pregnancy. Ultimately, it is up to patients to decide what is best for their bodies.

What constitutes evidence?

Even if we put aside the question of study design, there is also a significant question of outcome. How do we decide if an abortifacient is truly safe or if hormone therapy truly alleviates gender dysphoria?

It should be obvious that the alleviation of dysphoria is the primary therapeutic benefit of gender-affirming care, but even this has been called into question as people like Dr. Hilary Cass of the eponymous review suggest that perhaps future employment, sexual gratification and even whether we “get out of the house enough” might be better outcomes of interest upon which to evaluate gender-affirming care. Perhaps this moving of targets is motivated by the fact that transgender people consistently report higher levels of satisfaction with our care than nearly any field of medicine, and vastly lower regret rates relative to common surgeries like knee replacements, and even breast augmentations performed for cisgender women relative to the same procedures performed for transgender women. And this isn’t rocket science, but for those of us who desire medical transition, it is the only thing which reduces our experience of dysphoria as well.

But what is not in question, no matter what Chief Justice Roberts or Justice Thomas or even Secretary Kennedy may say is that we ourselves are profound, incontrovertible evidence for the success of our care. My life, like so many others, is unquestionably better than it had ever been prior to transition.

And every day I thank God or Darwin or Marie Curie that medical science chose to value my happiness over cheap political points.

Epilogue:

In mid-August 2025, Gordon Guyatt, whose GRADE standard was discussed earlier recently broke ranks with the right-leaning organizations that had been most vociferously lauding his work. In a public letter released on the McMaster University website, Guyatt and the majority of his team wrote:

“We therefore feel compelled to make explicit our view regarding how our findings should and should not be used. Following fundamental principles of humane medical practice, clinicians have an obligation to care for those in need, often in the context of shared decision making. It is unconscionable to forbid clinicians from delivering gender-affirming care.”

Grateful as I am that Guyatt and his team chose to finally take a stand, it’s hard to describe the conflicting emotions this pronouncement evoked. Guyatt, whose team conducted their own reviews on gender-affirming care, claimed that he was not aware of any significant anti-trans bias from the organizations that collaborated to produce the reviews. He believed, he attests, that the pursuit of science is an apolitical one, and that his team entered these politically contested waters in the name of empiricism. And that may be true. But it’s also true that the Miroshnychenko review of which he was a co-author was commissioned by the same SEGM mentioned above. SEGM is a vocal opponent of gender-affirming care. During the same conference in which Riittakerttu Kaltiala lamented that an RCT for gender-affirming care would be impossible, other conference participants compared being transgender to a “communist” mass delusion. They likened a trans person’s belief in one’s gender to a belief that one is a bird, and compared gender-affirming care to encouraging that person to jump off a cliff with the intention of flying.

If Dr. Guyatt believes that this is the apolitical science of which he has always dreamed, we have a very different idea of what constitutes politics.

[1] For an exceptional analysis of the discursive tools deployed by the Cass Review to belittle transgender youth, I would strongly encourage people to look at Cal Horton’s paper The Cass Review: Cis-supremacy in the UK’s approach to healthcare for trans children, available here. A detailed analysis of the methods themselves and the scientific pitfalls of the report can be seen here. Although not peer-reviewed, perhaps the most widely known critique can be found in the McNamara et al (2024) Yale Report.

[2] It’s generally agreed that an RCT is inappropriate for GAC, but one possibility is a waitlist trial; which provides a natural control group. While some WCTs involved the intentional randomization to waitlist before treatment, they can also occur naturally when the need for care is greater than the availability of providers. This is where compromise promises the most ethical possible outcome: without adding increased suffering, we are able to leverage a systemic limitation into a natural opportunity to test our research question. While randomization and an intentional delay might offer control over variables which have the potential to cloud the final dataset, these would occur at significant human cost likely far in excess of the ostensible benefits.

Interestingly, one study did accomplish a randomized control trial through similar methods as described above for adults. The study examined the effects of testosterone therapy by assigning a 3 month waiting period for one group of patients, and no waiting group for another. Aside from sample size, the major critique has been that this was an “open label” trial, meaning that participants were aware of which treatment group they’d been assigned to. This is not a surmountable barrier, as even with the use of a “sham drug” (which would be grossly unethical) the virilizing effects of testosterone would be impossible to ignore. The study unsurprisingly found that earlier access to testosterone had positive effects on gender dysphoria, quality of life. The limitations of this study and the question of open-label trials for GAC is explored in this AMA Journal of Ethics article.

[3] We prioritize the prospective study over the retrospective one because of inferences we make not about cause and effect or measurement, but about honesty. A prospective study where data collection, study aims and analysis plan is able to be registered beforehand allows us to hold study teams accountable for deviations from the protocol. In a retrospective study, the outcome of interest has already occurred, and in most instances, data has already been collected (survey methods allow for the potential that data collection can occur later, but this is subject to recall bias and therefore collecting data after the decision to engage in a study alone does not mitigate the effects of a retrospective analysis). In these circumstances, we cannot also randomize. But randomization is also not always possible, nor, it must be said, does it exist as a panacea for all ills that might plague data integrity (see Dr. Kaltalia’s statements above).

Related posts