How to identify anti-LGBTQ therapists

Keeping LGBTQ people safe from predatory practitioners

Jessica Kant, LICSW MPH

After I started speaking about the problems of online therapist directories, parents began reaching out to ask how to find an affirming therapist. While in many places like New York City or Los Angeles, there are a huge number of prominent, loud and proud queer therapists, this isn’t always a feasible option. For one, many people live in an area without such a surplus of affirming providers, and while there are affirming providers everywhere, LGBTQ-specific providers are making themselves decreasingly visible as they’re targeted for online harassment campaigns, especially for those of us that work specifically with transgender youth. Second, regardless of where you are, we are facing a therapist shortage across the United States.

Taking all that into mind, my response as a result is generally that for the majority of things a person might want to see a therapist, finding a good therapist is probably enough so long as you know what to watch out for. Not everyone needs to specialize in working with LGBTQ+ youth, and this is especially true if your child would benefit from specialized care — such as someone with substance abuse training or experience with complicated grief and bereavement. Every additional layer of specialization decreases the number of available options in an area, so while all of us want to see someone who is an expert in all arenas, we’re often forced to choose the person who has expertise in a single domain, and recognize that there may be growing edges along the way. Therefore, the question inevitably then becomes: in looking for a therapist for my child, how do I know what to avoid?

Rejection of standard language

One of the most clear hallmarks of a non-affirming (or vastly undertrained) therapist is a reliance on less-common or outdated terms that no longer comport with the current standards of language. While admittedly, language shifts frequently and often there may be two people who prefer two different terms, where this differs is emphasis. Therapists should quickly learn to match a client’s own voice, and adopt the terms they use for their lives. In other words, therapists: if a client describes themselves as bisexual or pansexual, then use that term.

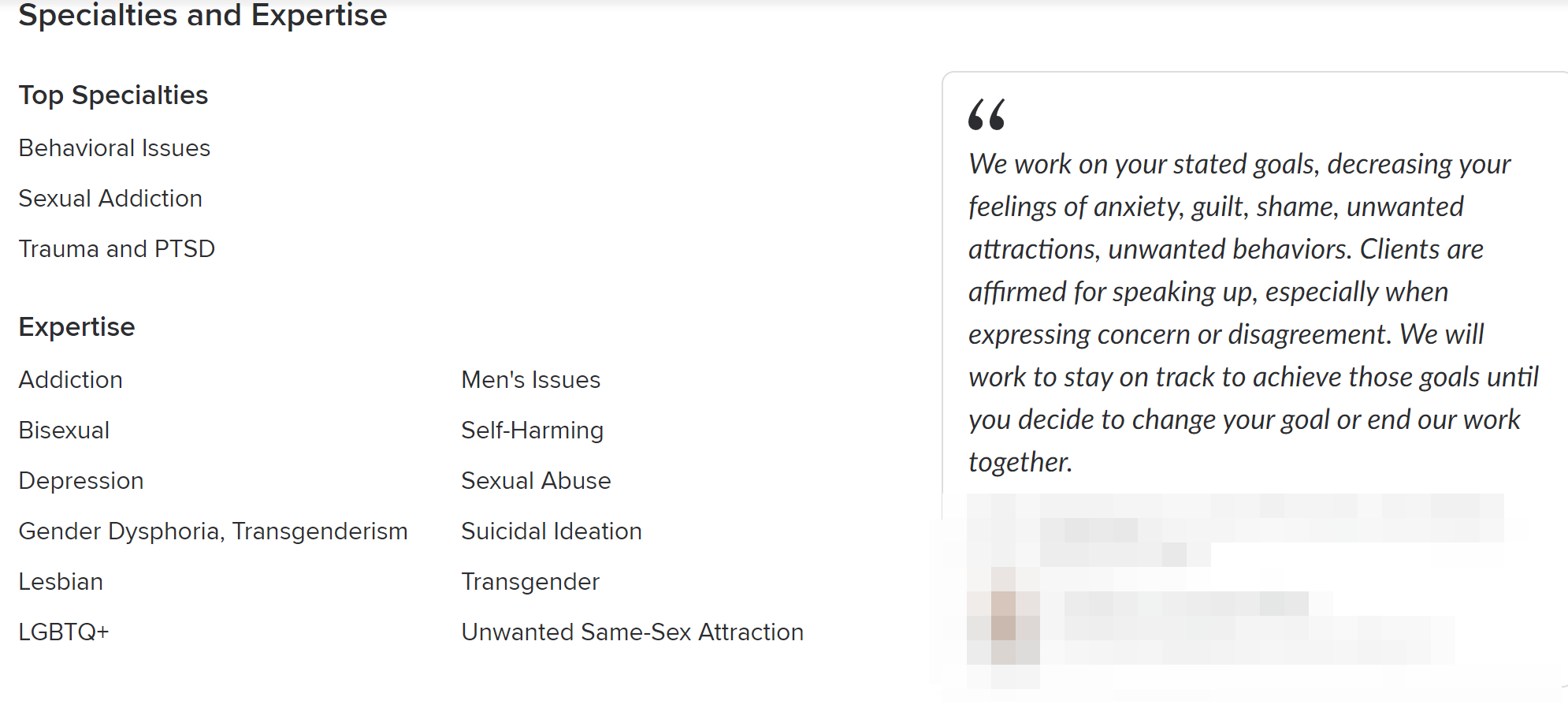

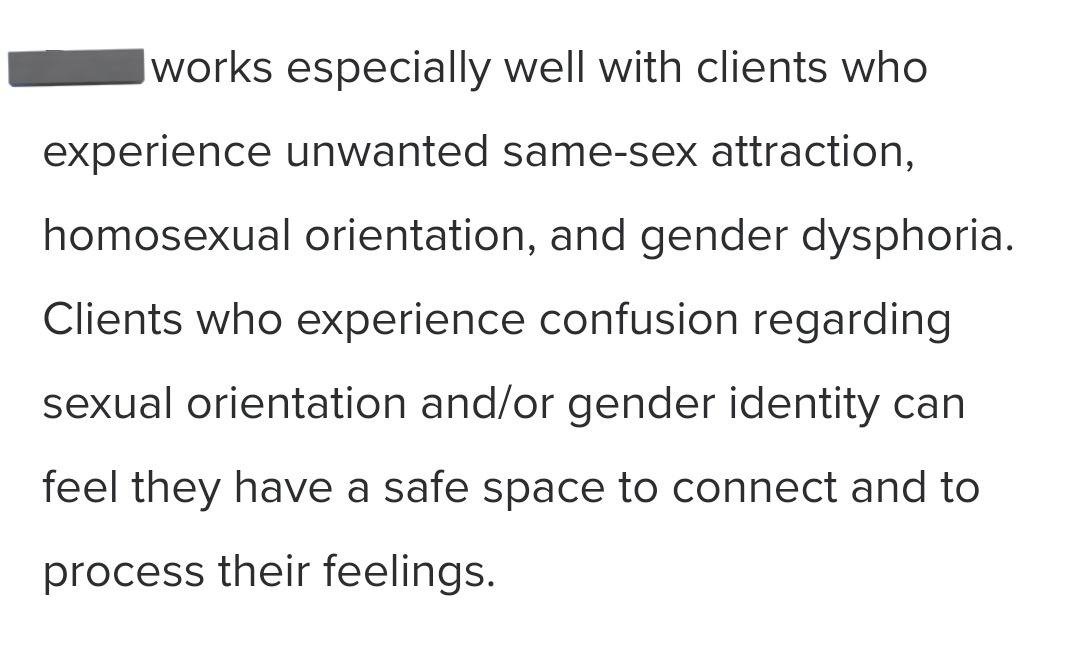

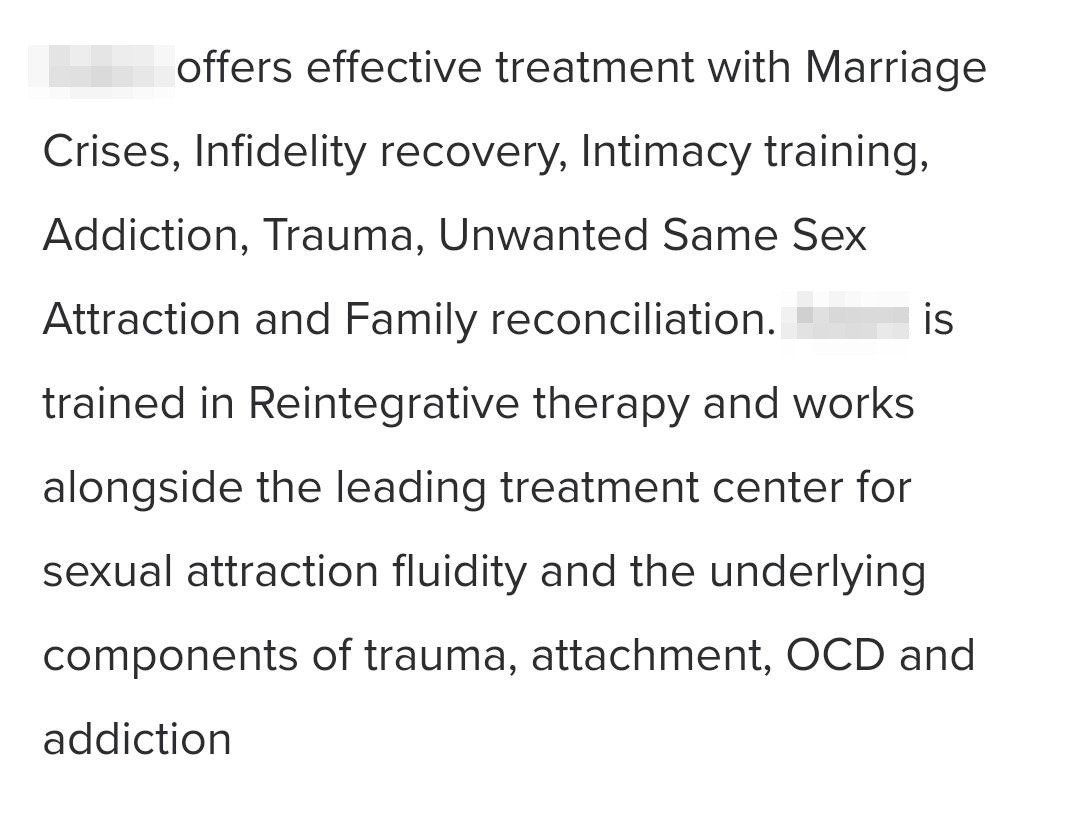

This has been most evident with the insistence of conversion therapists on using terms like “same-sex attraction” to describe anyone who doesn’t conform to a heteronormative lens (eg, anyone lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, etc.) While sometimes this is used for precision in conversation, it’s cumbersome to use all the time. If nothing else it’s a matter of sheer number of syllables (especially where the word “gay” will suffice).

This is most obvious when providers will never use words like gay or trans, or who overly emphasize the difference between behavior and identity. While it’s true that in healthcare and the social sciences, we often discern between the two as a means of being more inclusive towards people who engage in a specific activity but are not ready or interested in making this a core facet of who they are, it is also true that there are protective benefits to such an identity. A large part of the gay rights movement of the previous century was predicated upon the idea that there is power in identity, as shared identity creates community. Ultimately, it’s community that helps us find our people and keep us safe. Providers who seem hung up on differentiating between behavior and identity, when such differentiation is not at the behest or lead of the client, may be trying to drive a wedge between these two concepts based upon their own moral judgment, not what is best for the client.

Similarly, contrary to the assertion of anti-trans groups, there is no evidence that using client language “concretizes gender identity” or sexual orientation. Both of these things can change and fluctuate over time, and that they do is not evidence that something is wrong. If a therapist refuses to use your child’s chosen name– even if using it is difficult for you as a parent given where you are in your own journey of discovery, this can be a warning sign in a provider. At the very least, it’s a sign that your child may soon refuse to return to therapy. Therapeutic alliances are built on respect, with the onus of that respect on the therapist themselves.

If a therapist refuses to address someone by the name and pronouns by which they wish to be addressed, it’s unlikely this alliance has any chance at all to grow. Even if your child is going to a provider for unrelated reasons– such as impulse control or depression, neither of these things are going to be addressed successfully in therapy until the therapist shows they can respect youth for who they are and how they want to be seen.

In this way, it is irrelevant how a therapist personally understands a person’s gender. Using their chosen name costs nothing and can make the difference between a successful alliance and a child forever closed off to the idea of psychotherapy again.

Some of the more subtle turns of phrase that are worth monitoring may include an overemphasis on including the word identity, such as supplanting “trans youth” with “trans-identifying youth”. While this can be benign and many affirming therapists may judiciously choose to include “identifying” to drive home specific points (I do at times), if your child is transgender and your therapist will only say “trans-identifying”, it may be worth having a direct conversation about this. If you personally are struggling with this, while there are legitimate criticisms of this umbrella term, “gender diverse” provides a non-judgemental alternative.

Other more clear indicators include the usage of clinical-sounding pseudoscientific jargon such as “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria”. ROGD is a debunked hypothesis put forward by anti-trans groups to delegitimize the apparent rise in openly gender diverse youth. Adherents reject the idea that decreasing social stigma may play a role in the rising number of out trans and nonbinary youth, and instead blame “social contagion”. If your child’s therapist uses the term “social contagion” in conversation, this should itself be concerning. Because while social contagion has been used, for example, to describe the alleged clustering effect of youth suicide, modern epidemiological research calls this idea into question. Rather than a “contagion” explaining groupings of youth who attempt or complete suicide, youth who are exposed to peer suicide may be more likely to attempt suicide themselves if they are already at risk and farther along in the process of contemplation. Few, if any, will spontaneously decide to attempt suicide out of nowhere. It is reasonable to assume that those that do are already struggling with something for which intervention is already long-indicated. While not comparing the experiences, it is true that those who already experience gender dysphoria or discomfort in one’s birth-assigned sex may find the presence of other gender diverse youth gives them the courage to explore their own experiences and identity further.

The existence of other trans youth doesn’t create more trans youth, but they do increase the chance that trans youth who are not already out will consider coming out at least to their peers. While some “emotional contagion” research is out there, it is quick to distance itself from the claims attached to ROGD and similar ideas. Rather, these are scientists looking at specific processes within recursive human interactions that influence how people experience or react to a given situation. In other words, anxious people make other anxious people more anxious.

The biggest warning sign:

If a therapist refuses to address someone by the name and pronouns by which they wish to be addressed, it’s unlikely this alliance has any chance at all to grow. Even if your child is going to a provider for unrelated reasons– such as impulse control or depression, neither of these things are going to be addressed successfully in therapy until the therapist shows they can respect youth for who they are and how they want to be seen.

Overemphasis on etiology

Etiology is a word for how we conceptualize the origin of an illness or clinical presentation, and it has a complicated history in psychiatry. A hundred years ago, etiological explanations were psychoanalytic in nature, tending to place the origins of illness in early childhood experiences and internal struggles between drives and complexes. As science evolved and psychoanalytic theory has been replaced with newer and better frameworks, so have the explanations for most experiences for which someone might want to visit a therapist.

As a result of this, in modern therapy there has been a de-emphasis on etiology itself, and where etiology is important, we now prioritize client understanding of the problem as well as biophysical explanations based on evidence gathered in the past seventy years. Similarly, with the genesis of Family Systems Theory, we have a better framework for understanding how these relationships influence our perceptions and behaviors, and can contextualize these influences outside of the narrow frame of “drive theory” and ego psychology (core components of psychoanalytic and much psychodynamic theory more popular in the earlier days of psychotherapy).

Sometimes we also don’t even necessarily need to know what causes something to offer relief. Even PTSD– which has a clear etiology based in the interlocking relationship of experience to environment– can now sometimes be treated with a modicum of success without the therapist even knowing the originating incident or incidents. It is often through the course of building a supportive space and getting to know a client that therapists learn kernels of information that help describe the general shape and outline of a trauma without knowing the very specifics.

However, those who seek to change people for characteristics they might find undesirable like sexual orientation and gender identity put enormous emphasis on how they understand the origin of these experiences. While neither being gay nor being transgender are illnesses, to them they are, and in order to “treat” them, conversion therapists have long relied on the understanding that they are, and that they originate with trauma. People who disbelieve in the legitimacy of gender identity, for example, might choose to explain transgender boys and men as being “women who reject femininity”.

As described in a previous post, some of the most prominent religiously-motivated conversion therapists have long believed that non-heterosexual sexual orientation is inherently a product of trauma. For them, there is a natural progression of the human lifespan, and variations on this are evidence of a problem. It is okay to ask your therapist outright why they believe people are gay or trans. While there are lots of interesting half-cooked ideas about the topic, no serious scientist believes these. As therapists, we understand that it’s irrelevant: being LGBTQ+ is a part of the natural variation of human experience. The correct answer to “why is my child is gay” is somewhat tautological: “because your child is gay, and sometimes that happens. Isn’t that cool?”

It’s extremely important to understand that as therapists that we no longer view being LBGTQ as an illness — in fact, as a profession we’re quite ashamed that this was not the case in our recent history. While this is fairly simple for same-sex/same-gender attraction, a slightly more complex depathologization process has occurred for gender identity. Once called “gender identity disorder”, which was seen as an illness, we now differentiate between identity— which is not something that needs or should be “treated” — and dysphoria, the negative experience of feeling incongruence between one’s body and one’s affirmed gender. Outside of the United States, this is frequently called “gender incongruence”, as it speaks to the unique distress of the difference between one’s natal sex and the sex typically associated with a given gender. The hope of treating gender dysphoria is not to change identity, but rather to minimize distress. This is why unlike conditions such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder for which surgery is contraindicated, the treatment for gender dysphoria may very well involve facilitating physical changes which we call embodiment goals. However, there may be other ways to minimize dysphoria in conjunction with medical interventions in a fashion that is potentially more beneficial than medical interventions alone. This, however, should be up to the client. Nevertheless, for those who desire a body more aligned with features typically associated with their gender, there is no evidence that therapy alone is capable of reducing distress in a fashion remotely commensurate with embodied interventions like hormones.

Identity is not pathology:

It is not unusual for people to have multiple diagnoses, and multiple diagnoses alone are not an indicator of a problem as few diagnostic codes explain all of the things for which someone might present to therapy, Therefore, if your child’s therapist diagnoses them with gender dysphoria and ADHD, this isn’t itself a cause for alarm. If they suggest that ADHD caused Gender Dysphoria, this is cause for alarm.

Muddled differential diagnosis

It is not unusual for people to have multiple diagnoses, and multiple diagnoses alone are not an indicator of a problem as few diagnostic codes explain all of the things for which someone might present to therapy, Therefore, if your child’s therapist diagnoses them with gender dysphoria and ADHD, this isn’t itself a cause for alarm. If they suggest that ADHD caused Gender Dysphoria, this is cause to find a new therapist.

The history of “diagnosing” LGBTQ+ people with a psychiatric condition based purely on who they are can be traced all the way back to Freud, but it is mot notable in the history of the diagnosis of “Borderline Personality Disorder”. Borderline Personality Disorder was historically given disproportionately to lesbian and bisexual women partly as a product of the inclusion of “promiscuity” as a diagnostic criterion. Research and our own experience of the world under patriarchy tells us that women who have multiple partners are far more likely to have that scrutinized than the same behavior for male peers. This is potentially even more true for bisexual women, who have had our sexuality pathologized as licentiousness. Curiously, while women have historically been far more likely to be diagnosed with BPD, prevalence studies have also shown a greater incidence of the diagnosis among gay men compared to gay women when looking only at samples of LGBTQ people. This may also be reflective of a similar bias.

A differential diagnosis, as it is in medicine, is a process of sorting between multiple plausible diagnoses to find the best possible name for what a client is experiencing. While for many conditions, a clear differential is less important than how a client wants to use therapy as a space for healing, there are some conditions for which an accurate diagnosis significantly changes how therapy should go according to best practice. For example, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) functionally look very similar, and may describe a similar experience for the person experiencing them. However, a review of the evidence to date suggests that one of them is far more amenable to specific cognitive behavioral interventions such as Exposure and Response Prevention Therapy. While many people with GAD find exposure therapy helpful, exposure therapy is the gold standard for OCD – and exposure therapy for the two conditions is a different process.

If your child is diagnosed with a condition, and you suspect the motivation is identity-related, ask your child’s primary care provider to explain the diagnosed condition to you. In some states, “expert” witnesses with no actual expertise in gender care have posited that conditions as blatantly unrelated as Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) may be “underlying causes” of trans-ness. None of them have ever been able to posit a viable explanation for how the one could lead to the other, although several have tried.

You can start by asking them to explain the connection. Modern conversion therapy frameworks claim that neurodivergence might predispose children to isolation or social ostracism, pushing them to find other points of connection with peers. While this is an explanation, it isn’t a good explanation. In the case of sexual orientation, we know that despite thousands of years of people trying to force gay people to be straight, this has never once been successful. It has been equally unsuccessful for people to will themselves into heterosexuality; many adult-oriented conversion therapy frameworks attempted exactly this. The reverse is also true, no one can will themselves into being gay or lesbian. For gender identity, this is even more implausible. Contrary to popular talking points, despite the increase in inclusiveness and visibility, few youth live in an environment where being a gender minority would confer more positives than the inherent negative social pressure to be cisgender.

Finally, it is possible to simultaneously experience conditions like Body Dysmorphic Disorder alongside gender dysphoria. This does not mean, however, that any link between the two exists. This is true in the same way that one can have a sinus infection and still be bisexual. However, there are cases where BDD might exacerbate gender dysphoria. In these circumstances, although rare, it is essential that people seek therapists who have worked with transgender patients who experience BDD. Threading the needle between dysphoria and dysmorphia is difficult but important. Failure to distinguish between the two may aggravate both.

Emphasis on discipline and control

Anyone who has ever done family therapy will tell you that rarely do adolescents respond well to discipline and control. While there are times where caregivers need to set limits and enforce family rules, doing so is a precarious task. Contrary to the advice of previous decades, we know that children of all ages respond better to positive reinforcement. While this isn’t always possible and there are clear times that safety dictates privileges must be taken away or reduced, this is a choice of diminishing returns– especially as kids get older.

While Structural Family Therapists may place renewed emphasis on the executive functioning of a family, they do so to correct identified imbalances in power. Structural therapists do not, however, impose rules for the sake of rules and hope for the best. However, lately a cottage industry has been growing of parental advice for gender diverse and gender-questioning youth. While many of these are informal in the case of online peer support forums like Mumsnet in the UK, others are how-to guides written by people exiled from or adjacent to the field of psychotherapy. One guide, put out by Erin Brewer and Maria Keffler encourages the total removal of children’s peer groups, and heavy monitoring of their social media presence. These suggest that the “total isolation” of children away from the influence of their peers “may be necessary”, and advocate for the removal of “cross-gender” items from children’s possessions.

The overexertion of authority over youth rarely ends with acquiescence, and tends to culminate in hostility, arguments and indignant opposition. On a long enough timeline, this can look like estrangement or alienation. While some of these are unavoidable in the process of raising adolescents, the latter are not. No one who suggests that the total estrangement of youth from their families is an acceptable risk of “setting limits” has their best interest in mind. As hard as it is for many parents to accept, adolescence is a time where we tell our families who we are — not the other way around. Our role as adults in that process is to join them in that journey, and decide how much of a role we want to play moving forward. What we cannot have is total control and connection.

Appendix: screenshots of non-affirming therapists listed on Psychology Today

Further reading & resources:

-

While by no means authoritative, I’ve compiled this resource based on questions from students and colleagues trying to understand contemporary conversion practices and how they fit into the broader historical landscape. It’s a primer I hope to keep adding to.

-

Psychology Today is far and away the most popular means for prospective clients and patients finding therapists and prescribers (e.g., psychiatry, PMHNPs, etc). But it has a surprising lack of moderation, and conversion therapists are practicing out in the open. Here’s how to spot them.

-

Rather than focus on specific types of conversion therapy, the fundamental question parents should ask for their LGBTQ+ child when finding a therapist is whether this is someone who will see them for who they are. This guide talks about how to recognize red flags.