The stress response

A lot of people don’t realize just how connected our brains actually are to the rest of our bodies. Our emotions don’t exist in a vacuum, and while our feelings can take a toll on our bodies, the reverse is also true: when our body is struggling, it’s likely showing up in our emotions as well.

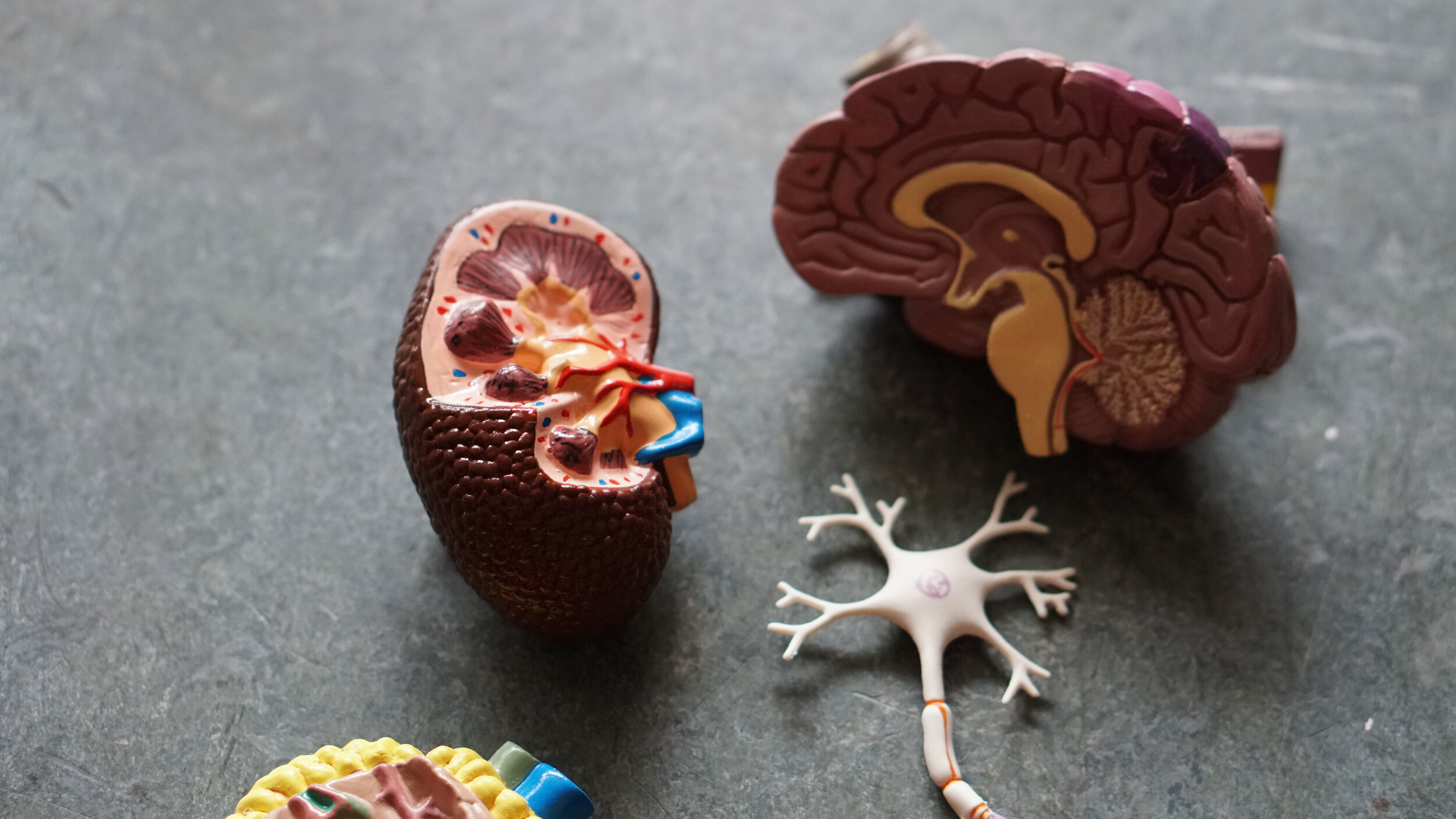

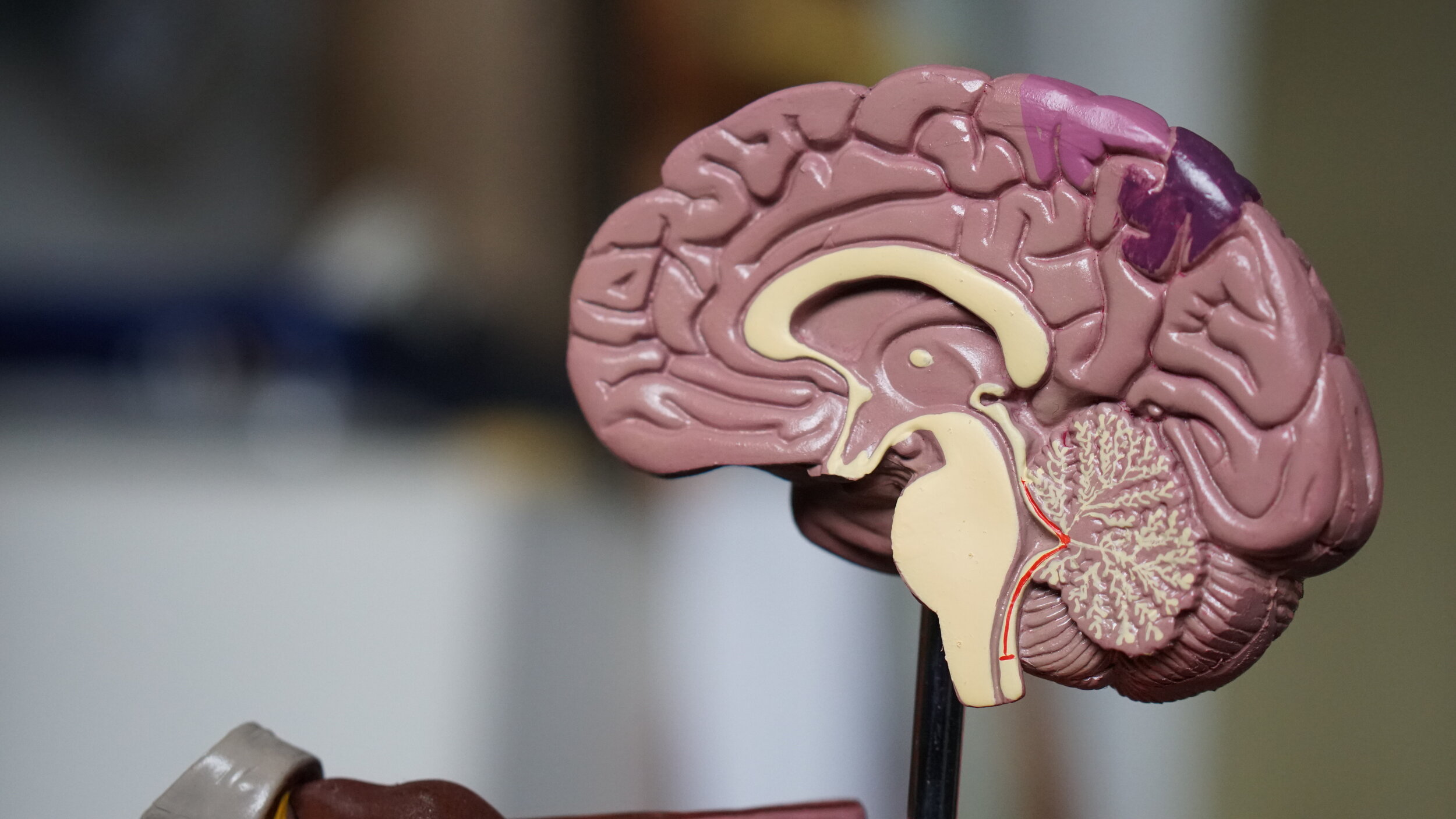

In fact, there’s a reason your body hurts when you’re upset or why some people get short of breath when they’re experiencing anxiety. In the center of our brains, nestled inside the brain stem, is our autonomic nervous system (ANS). While the medulla oblongata is largely responsible for involuntary muscle movement such as breathing and heartbeat, the ANS can speed up or slow down any or all of these functions depending on the situation.

Fear

Imagine for a minute you’re walking in the woods and you see a bear. It’s big and fluffy and slow, but it also has jaws that could rend a car tire in half without breaking a sweat. Your brain likely clocked the bear first; you’ll know because you suddenly feel that peculiar cool/hot sensation of an adrenaline spike. The adrenaline spike, or “rush”, is the body’s way of preparing itself for battle.

Adrenaline prepares you to run and gets your heart pumping, while cortisol prepares you for the possibility that you may need to expend tremendous amounts of energy in fleeing to safety. Cortisol readies your body for attack, making you more resilient in the face of a dangerous assailant, releasing sugars (glucose) into your bloodstream so you have an easily bioavailable supply of fuel with which to do battle.

And this is exactly what the brain is supposed to do. The human stress response system, often referred to as the “fight or flight” response, is an adaptive mechanism that readies us for danger. But this isn't sustainable by any stretch. If our bodies were constantly on alert, our glucose levels would deplete nearly immediately, and our cardiovascular systems would be overtaxed to the point of danger. As a compromise, humans are imbued with the ability to scan for environmental threats and our amygdala-- the part of the brain that senses danger-- stands watch, ready to get us moving if it has to.

Now imagine that bear turned tail and ran as soon as it saw you. Within moments, you would be able to rationally tell yourself that the threat has passed and you should start to experience a slowing down of sorts. People in this situation often report being tired, suddenly overcome with exhaustion from having burned such an extraordinary amount of energy in such a short period of time. In extreme cases, our parasympathetic nervous system takes over and releases neurotransmitters like GABA or even painkilling drugs like endogenous morphine. People have been known to pass out after frightening encounters, not out of fear, but because their bodies are suddenly flooded with naturally occurring sedatives.

Stress

While our bodies can be quite deft at eliminating most toxins through the renal system, including those produced in a fight or flight reaction, the degree to which it is able to do so is dependent on a variety of other factors including the amount of water you drink or the foods you take in. Disaster protocols like Psychological First Aid often emphasize the need for healthy eating and regular water intake, while also stressing the need for sleep.

Contrary to the common assumption that sleep is a time where the body shuts down, sleep is actually the time the body does the most growing and repairing. While the efficacy of such a strategy is as of now undetermined, this is why some body builders have been known to (erroneously) microdose with melatonin prior to workouts in the hopes that they’ll be able to induce greater muscle development during exercise.

But our muscle and lean tissues aren’t all that are repaired during sleep: in addition to the litany of theories about the exact function of dreams, sleep is also the time the brain makes the majority of neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and dopamine, which are responsible for mood and pleasure as well as emotional regulation.

Unfortunately, in the absence of good sleep and diet, cortisol builds up in the blood, in turn attacking lean tissues and promoting inflammation in the body. People under severe stress often report that their knees or tendons get sore more easily. In addition to cortisol build up, these aches and pains may also be associated with posture. Humans in fearful situations will reflexively put their hands up to protect their face or chest. Over time, the constant pressure of keeping one’s arms up can lead to stiffness and fatigue.

Toxic stress

But what happens when your body thinks there could be a bear around every corner? Over time our bodies lose the ability to flush the stress hormones out at the necessary rate. This is exacerbated in environments where the stressors are constant, such as those working as paramedics or firefighters. In this case, the body maintains a steady supply of adrenaline and cortisol to the body, effectively putting your entire body on high alert without a plan to come down.

For many people in these situations, high cortical loads are so common that they may lack any sense of novelty: in short, people may not notice exactly how stressed they are. Studies have shown that living in an area with a higher than average frequency of sirens and gunshot noises can trigger a higher cortisol level in the body. When these stressors are chronic, the body loses the ability to get back to baseline, and establishes a “new normal” where stress hormones are constantly running through your bloodstream.

In the face of acute stressors, such as traumatic loss or sexual violence, the body may undergo severe changes in a short period of time. Unlike the events that lead to chronic/toxic stress, traumatic events are those that shake the way you see yourself in the world. While both toxic stress from chronic stressors and traumatic stress from acute stressors can cause physiological changes in the body, the treatment one might expect for these two conditions is often actually quite different. We will be exploring traumatic stress next.

© 2020, Jessica Kant, MSW, LICSW, MPH

← back to writing

References

Porter, R., Kaplan, Justin L., Lynn, Richard B., & Reddy, Madhavi T. (2018). The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy (Twentieth ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme.