Streamripping democracy

Tips for watching the upcoming legislative season: tracking livestreams, legislative sessions, and senate hearings.

Happy new year! It’s been a while since I did a more tech-focused post that wasn’t specifically about misinformation in the media, and I’m not sure I’ve done a tech how-to yet, so please let me know if there’s anything I should change.

If this is useful for you, please drop me a line! The code that formed the genesis of this particular post came up initially out of necessity, then curiosity, and finally because it’s very hard for me to stop poking at puzzles once I start them. If you’re like me, you learn best by following along, so I’ve created a menu to the right with a handful of states. Find one you’re interested in monitoring this legislative season, and follow along.

Introduction

It’s hard to summarize 2025, but suffice to say a lot happened, and an awful lot of it happened all at once. Just as we needed to have all eyes on every hearing and proceeding making sure something roughly resembling democracy survives the next few years, reports began raising alarms about huge amounts of content disappearing from the internet. This was especially true related to past administrations, but also extended to unexpected categories like purges of medical information from the National Institutes of Health as I talked about here. While people scrambled to the livestreams and, whenever possible, posted updates as they happened, the sheer size and scale of the project was too much for any one person. Even the most well-resourced groups felt a strain this year trying to keep up with the pace. One of the side effects of this has been a renewed interested in amateur archivists who preserve history as it happens. As Decemeber draws to a close, and I think about what I have to add to the moment relying on the lessons from last year, what came to mind was that we need to get as many eyes on the system as possible.

As you are no doubt aware, potential bills in the United States are pre-filed throughout the year with the highest concentration typically in late Autumn. Early January marks the beginning of most legislative sessions, with the first few weeks tending to naturally focus on those that were filed in advance. Over the last eight years, these have tended to be the “culture war” bills which target minority groups and advance strictly partisan agendas.

For the few brave souls that do follow along during the initial onslaught to identify new threats against our communities in real-time, there are always more hearings than people. Suffice to say, we’re in an “all hands” situation at the moment, and in light of that, this tutorial will talk about the various ways federal, state, and city governments within the United States choose to display information related to public hearings and legislation.

My aim is to expand upon what exists already by adding an overview of how states serve this content, available pre-existing tools and a handful of command-line shortcuts that will help users stream, rip, and transcribe these hearings to make them more transparent and more accessible to the wider world. Feel free to reach out if there’s a particular platform that isn’t covered or you would like to see. As always, none of this is intended to violate state or federal law so please observe local regulations.

The basics

As of 2025, nearly all state legislatures stream and/or archive their hearings, and some allow you to download them directly from the site. I’ve created a dropdown menu to state legislative bodies below. Select a state and the menu will take you directly there so you can follow along.

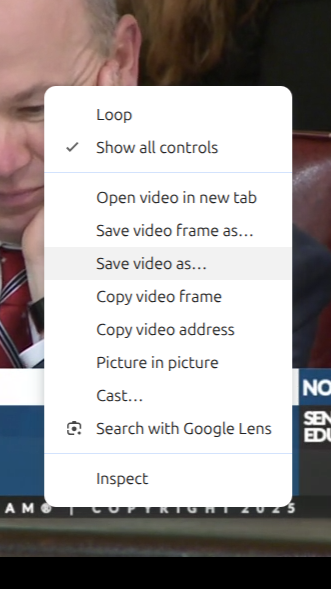

Regardless of where you are, there are many ways to watch bills and hearings, and while they’re at times painfully boring, sometimes it’s testimony on the floor or comments from the board that matter most, and when you spot something, being able to document it can be extremely important. Some states like as Massachusetts self-host archived sessions as fully-contained video files you can right-click and download right from the contextual menu like any other file. It’s not always that easy, however.

right-click menu on Massachusetts legislature archive page.

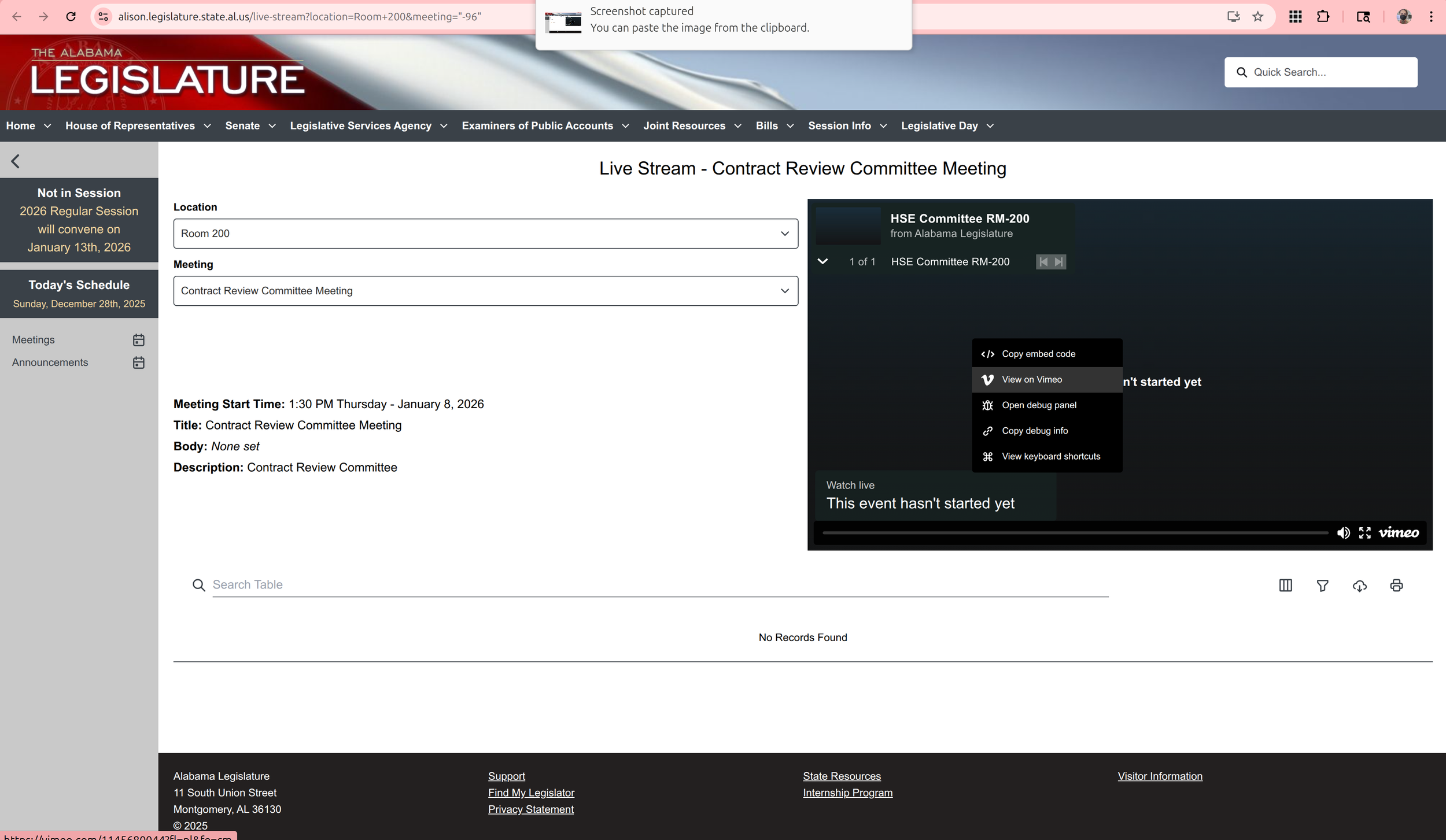

Alabama uses Vimeo. Clicking through to their account gets to all streams

In states fully committed to accessibility and transparency, these either include the closed captions or they are embedded directly in the video files. Both options have their advantages, but all states should realistically have a fully-downloadable transcript if we were truly committed to the principles of accessibility and transparency. While Massachusetts has the captions embedded directly into the video files, these aren’t searchable as an index while means uses who want to skip around to specific topics or see if an issue was discussed have to watch the whole video. This is extraordinarily time consuming. Aside from the accessibility issue, it' also makes remote content analysis difficult for people trying to monitor the machinations of local government.

This post will touch on various accessible streams in different states, and when the above accessibility or transparency features aren’t available, I’ll go over how to create them for yourself.

Congress has one of the largest hosts of transparency features, with the federal register and congressional record serving as a searchable ultra-index. For example, using this search bar below the Senate livestream, you can search all hearings and transcripts for sessions containing your search parameters. Starting in the late 1970’s, the Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (aka C-SPAN) was created to make the workings of government visible to the public (see the highly comprehensive Wikipedia entry for more). This still exists today, and both Congress and the Supreme Court are regularly streamed unless the hearing is classified or otherwise private. Nearly all are available on YouTube as they happen, many streamed by the Library of Congress.

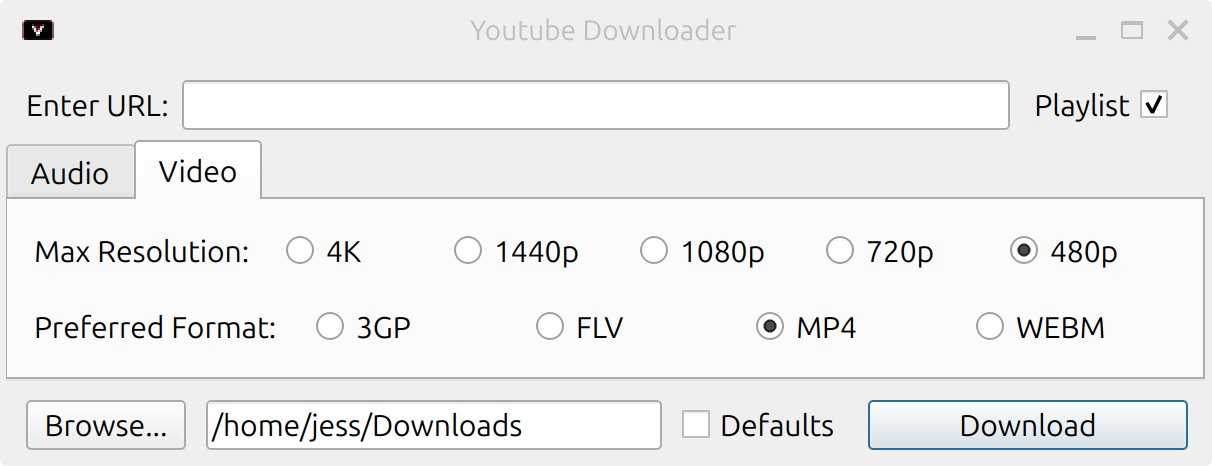

With respect to these, packages like Youtube-DL allow you to easily download them with a straightforward text-based interface, although Google/Alphabet keeps changing how they serve videos in an attempt to break downloader tools. Updates are regularly pushed, although your mileage may vary as monetization increasingly incentivizes them to crack down. I would recommend using a Github repo, like github.com/ytdl-org to ensure that patches are pushed in a timely fashion.

Unsurprisingly, many states use common social media platforms as well. Kansas uses Youtube to stream hearings, while Alabama inexplicably seems to use Vimeo. There are a variety of streamrippers available online, so I won’t go into them in detail. That being said, most of them are crawling with malware so stick to FOSS, especially github. While yt-dlp has gone through many revisions, most of what we’ll do after this portion of the tutorial will use a similar technique to how the script works. There are also graphical interfaces.

If you’re already familiar with the command-line and you would rather use a CLI tool, paste this into a shell or directly into your bash/zsh profile. It relies on just common packages most terminals should come with pre-installed, alongside FFmpeg, which can be downloaded here. FFMpeg powers audio/video for many modern operating systems, and may already be installed as well. When you want to grab the video, paste the URL directly into the prompt. FFmpeg will do the rest.

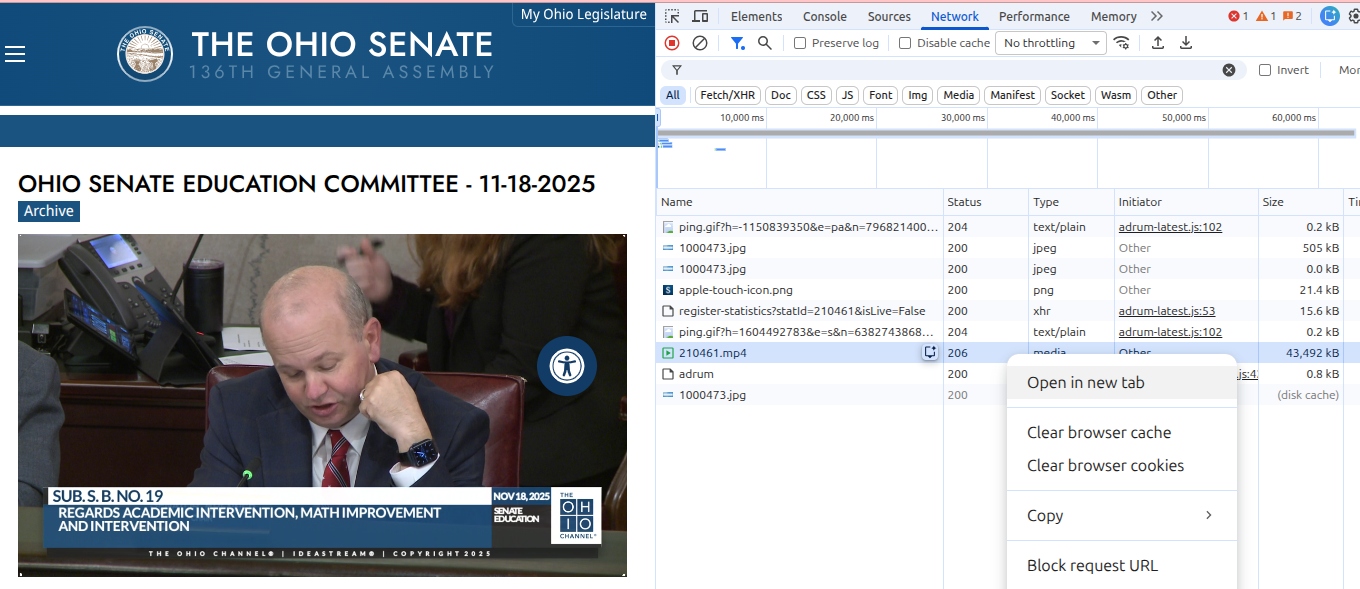

DIY streamripping in Chrome

Sometimes, all you want to do is grab the video and go. For self-hosted states, like Ohio which uses JWPlayer to serve video content, just navigating to your browser network sources tab can be enough (Ctrl-Shift-C). As with Massachusetts, right-clicking is really all there is to it. This time with the added step of needing to find the source in the “network” tab.

Archived stream from the Ohio Senate Education Committee

Additionally, since Ohio is entirely self-hosted and has closed-captions, turning on the network monitor and watching for subtitles files lets us grab a transcript of the whole hearing in a few seconds. More on working with those files later!

For states which use proprietary software but serve remotely, if follow similar steps (open your browser source inspector, and toggle “Network”) and see a file that says “chunklist” or “media” and ends with m3u/m3u8, copy that URL and skip ahead. While most of the options from here on out will focus on using a free open source video software package called FFMpeg, that doesn’t mean you have to use the command-line. If you’re feeling less adventurous, you can use a graphical interface like WinFF (Windows) or QWinFF (Linux + Windows). New Jersey is one such state.

New Jersey State Legislature livestream archive

-

Windows

Linux

sudo apt-get install ffmpeg curl jq

MacOS

brew install ffmpeg

Using ffmpeg, we can use the URL of the m3u8 file as a source location and output it to a complete mp4, with:

ffmpeg -i [stream] -c copy output.mp4

After that, let it run! Since this is a 5 hour video, I’ve clipped the other 30 minutes of virtually identical terminal output for both of our benefits.

Many state legislatures, such as Arkansas and Montana, however, use software called “Sliq”. It is also used by city governments and other state functions like school boards.

Sliq’s media platform is relatively comprehensive. It allows anyone to livestream hearings and/or stream archives in both video and audio, as well as access the agenda and any handouts presented during the day. With a few exceptions, however, it makes saving the video quite difficult if the admin hasn’t chosen to make it available. Sometimes it’s possible to grab the stream using the inspector as shown above, but sometimes you’re in a hurry.

The following shortcut will turn “grab_mp4” into a command you can toggle any time. It will prompt for a URL and search the contents for the playlist. It then pipes that into FFMpeg, similar to yt-dlp above.

Under the hood of the Sliq “PowerBrowser”

So how does Sliq work? Similar to other types of streaming (eg, YoutTube) the stream is served in 10 second clips, typically labeled “media_ts” by default. When a user clicks on the livestream, it requests an .m3u8 playlist file. These types of files were originally used to serve songs and other recordings in a particular order during the beginning of internet radio stations, notably, created by WinAmp. An m3u/m3u8 file is not itself a media file, but rather a track listing pointing to the location of source files. In Sliq’s case, these are broken down into the aforementioned chunks, and served up consecutively. However, users can bypass the instructions to serve then one after another, and instead request the location of all chunks, request these, and them transcode them as a unified movie file on your computer.

In some instances, such as with a livestream, a placeholder URL may stand in for whatever is broadcasting live. In that case, we can take advantage of the “location” (-L) argument in cURL, and instruct ffmpeg to encode as it goes. The following is an example of the Arizona State Legislature’s livestream, at azleg.gov/actvlive. Using a modified version of the code above, we can pass the target URL into curl but instruct it to follow the URL to the destination, parse the playlist URI and pass that to ffmpeg.

Since in some cases, multiple streams will be served at once, I’ve also added a version of the shortcut with the “translate” command added to the pipe, which converts apostrophes to new lines, making it easier for grep to sift through the output.

While most implementations I’ve seen of Sliq don’t share transcripts automatically, that’s not universally true. When they aren’t shared, however, a side effect of how Sliq embeds subtitles can be used to pull out the text and search the contents. This code snippet, for example, can be used to print the subtitles to the console.

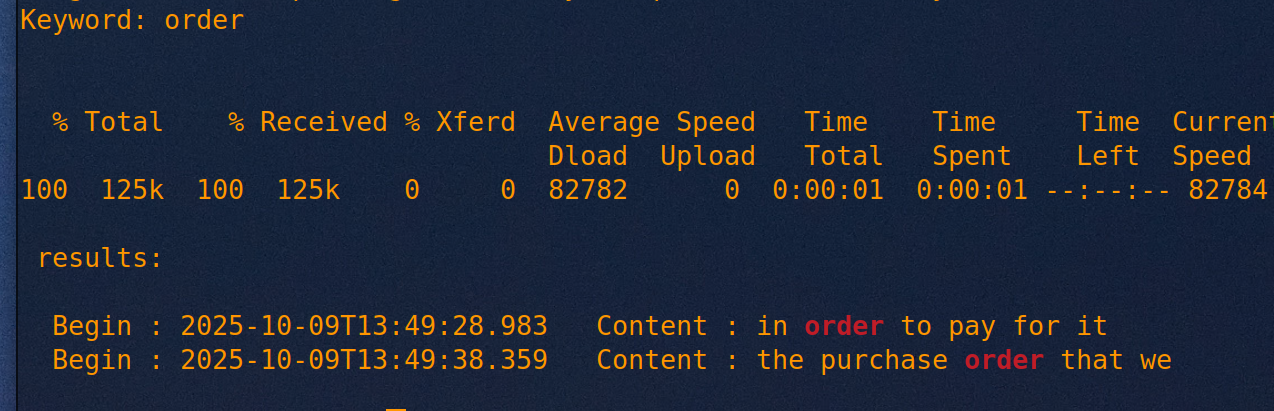

Let’s say you have 30 minutes and a 15 hour hearing and you need to know if the one you’ve chosen contains discussions about rules and procedures. We can use grep and regular expressions (aka regex), alongside jq to search the subtitles. Like the one above, this script will prompt you for the target URL, and for a keyword. In the example below, the script searched this 90 minute recording for every instance of the word “order” in less than 4 seconds.

What’s more, now that we’ve saved it as a shortcut using “alias”, we can run the script by typing “kw_s” into the terminal any time we want. While right now it’s mostly proof of concept, if you need to poke through a whole archive, this will save you potentially hours. Here it shows the timestamp on the video and the exact second where the word is used. In the event the word isn’t used during the recording, no results are shown.

But wait there’s more!

I’ll be releasing source code soon on github. Check back often or drop me a line if you have questions.