Re-authoring gender

I recently guest lectured in a colleague’s class on LGBT health, the topic of which was non-medical gender affirming care – or interventions designed to aid trans people in their journeys where HRT and medical intervention can only go so far. One aspect of this affirmation that I, and many others like me with similar theoretical frameworks rely on, is rooted in the practice of Narrative Therapy, in a process which Michael White called re-authoring.

Re-authoring is the process of exploring subjugated storylines buried by the dominant stories given to us by those in our lives with more power. It seeks not to replace or supplant dominant narratives, but rather to explore alternative ways of understanding more congruent to the people we know ourselves to be.

As White was fond of pointing out, our lives are a near-infinite number of events spreading through time and space, and when we tell the stories of our lives, we necessarily select from these points to create cohesive stories – but these are far from the only stories we can tell. Likewise, the same collection of memories can also be told differently, interpreted through fresh eyes, aided in this process by connecting to the ways we want to be seen by the world, to our own wishes for ourselves, our stories, and discursive control over the lives we’ve lived.

As I was explaining to the class the manufacturing of the current moral panic, I necessarily had to cover the idea of “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria” – an idea that has done more violence to the trans community than any other since Blanchard’s typology in the 1990’s. Predicated on the assumption that trans identity is an opportunistic contagion seeking out vulnerable youth looking for belongingness and meaning, it is based primarily on stories collected from parents in various stages of estrangement from their children. Aggrieved parents told Littman, whose study was based on the work of Jungian psychotherapist and fellow social worker Lisa Marchiano, that the onset was “nearly overnight”, with no visible signs of gender incongruence prior to the assertion of trans identity.

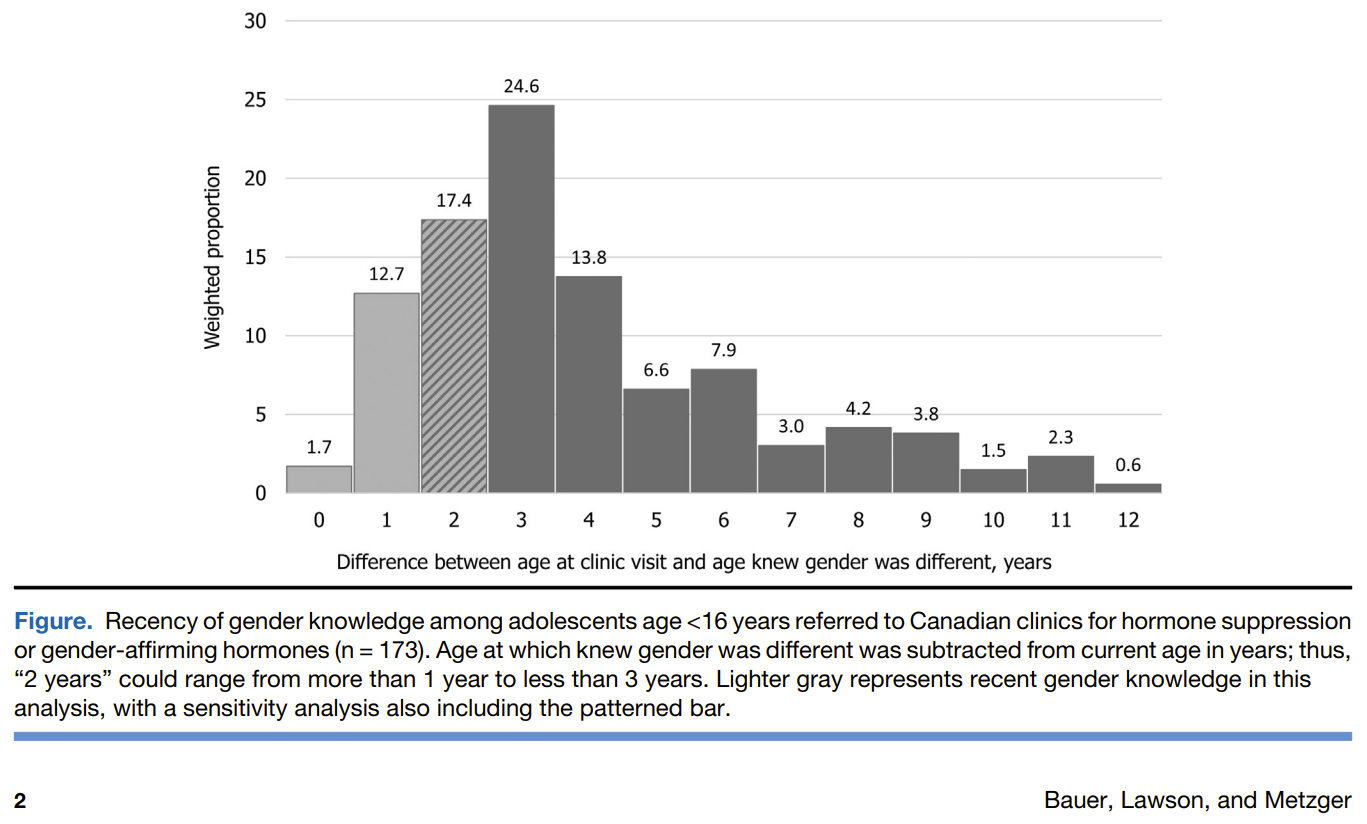

Bauer et al offered an alternative explanation: that perhaps what felt like it was overnight for caregivers was just part of a long, arduous process of self-reflection where parents are only brought in when a degree of certainty has been reached. This also explains the certitude with which parents were met from their children – this was not an overnight decision, but one stretching back years. And in fact, Bauer’s team found precisely this, with respondents in their dataset reporting as many as twelve years between initial self-knowledge and presentation at gender clinics.

And as I found myself explaining the evidence against this poorly-constructed theory, I also found myself reflecting on my own experience. For while this is only a small snapshot of the hundreds of times I was keenly aware of who I was, or more often who I was not, it’s just one of many memories that sets the time between initial self-awareness and presentation to a gender clinic at around twenty years. Twenty years is a lot of things, but “overnight” isn’t one of them.

I have this early memory of visiting my sister at sleepaway camp in one of the more strikingly beautiful parts of the bucolic northern New England countryside. As we pulled into the soccer field being used as a visitor parking lot in our family’s brick-red Volvo station wagon, we joined throngs of parents carrying care packages and cameras, bustling with excitement for a weekend of talent shows, horseback riding, and athletics. Dust clouds kicked up on either side of each vehicle, spreading hot Maine dirt into the air coating everything it touched, burning our eyes, and turning our shoes grayish brown.

My sister has always been my hero. Three years older, she was the person I’d wanted to be for as long as I could remember. She seemed rarely as happy as she did here, among a hundred other girls her age, laughing and seemingly freshly excited every time she saw another of the dozens of friends she’d made over the summer.

Campers slept in log cabins with a dozen or so bunkmates, each with their own steamer trunks full of supplies. The air was a strange mixture of fresh mountain air, New England humidity, bug repellent and sweat, mingled awkwardly with the sickly-sweet fruit body sprays so popular at the time. As I sat on my sister’s bunk and looked up into the rafters of the cabin, I saw decades of writing in over a hundred different handwriting styles, in-jokes, dates and special occasions; proclamations of lifetime friendship. Some were in that milky gel pen ink so popular at the time, others were ballpoint pens cutting into the timber. It was as much a tactile experience as a visual one. Generations of bunkmates making their literal mark on the world.

As I traced the round letters, punctuated by hearts or smiley faces or peace signs, I had this sudden feeling of overwhelming anxiety matched by a sense of profound loss I couldn’t explain, incongruous with the jovial atmosphere of family weekend. As my sister’s friends came by and introduced themselves and showed me around, I had this intense feeling of longing that wouldn’t recede. Later I would juxtapose my own brief experiences in an all-boys sleepaway camp with that which I’d felt that day, and could only feel a hollowness with no apparent cause nor end in sight.

As we drove off that day, I felt this incredible pang of self-recognition. Not only was my heart hurting from knowing I wouldn’t see her again for another month, I knew that I was leaving a place where if the dice had rolled only a little differently, I too would have been home. And I wept. I wept for her, I wept for me, and I wept because I didn’t understand what it was that was eating me alive.

There are hundreds of these stories, perhaps thousands. They remain filed away in dusty storage boxes in the least-used corners of my brain, and sometimes they spill open for no discernible reason. Memories are like fossils– imperfectly preserved in perpetuity, only to be excavated, often by accident.

Four years after visiting her summer camp, I met a girl named Jessica and had the inexplicable thought: “that’s the name I was supposed to have.”

It wasn’t true of course; later, when I came out to my family a full decade and a half after, my mom shared that “Jessica” was never on the list. If somehow my genes had expressed differently, if the gametes that went on to form the building blocks of my first cells hadn’t conspired against me, it still wasn’t one my parents would have chosen for me. But that didn’t mean I felt any less connected to it. Hearing someone say the name out loud made me want to turn my head in answer, and the shame at this self-knowledge drove me farther into a depression that had been eating at me for a very long time.

The story of my gender as told by others is one of nonconformity, appeal to masculinity, settling into adulthood and eventual, sudden upheaval. The ways others would tell my story wouldn’t include the times that I tried to ask about being trans with my first primary care provider at Fenway Health in 2009, who asked me if I wanted HRT and when I said I wasn’t sure, simply moved on. Or the therapist I went to who, when I told her I was thinking about transition often, asked “do you want a sex change?”, and how when I didn’t know the answer to that question, she said “let me know if you change your mind.”

Michael White wrote often of Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development theory, and how we need to scaffold our conversations to allow for us to traverse territory that might seem too big, frightening or nebulous to cross in one fell swoop. Just as Vygotsky observed that we need to learn smaller skills before we can take on bigger tasks— like learning the alphabet before we can read, sometimes when we invite people to tell their stories, the questions we ask are too big to cross in one step.

If my therapist in 2009 had asked me “how long has this been on your mind”, I might have told her about the time I came out to a friend at 15, only to binge drink myself to sleep to forget it had ever happened. Or how I had almost worked up the courage to tell someone even younger, but then I saw The Silence of the Lambs and collapsed into a puddle of self-hatred. Or, I might have told her about summer camp. But she never asked, and we never talked about it. The more I tried to broach the subject, the more she would ask larger questions until one day when the stakes were so high I confessed how vulnerable I felt when I shared my feelings about gender and she was quiet and gave no response, she answered with total silence for an interminable fifteen minutes.

That session cost me around $150 cash and the shame nearly killed me.

Addressing Spiliadis

I began this post with starting by talking about Narrative Therapy, and I would be remiss if I didn’t address Spiliadis, whose paper is widely cited as the first “real” Gender Exploratory Therapy paper, since prior to its publication it simply didn’t exist and was merely a euphemism for “watchful waiting”. It was one of the first to really drive home the fictional narrative in which “exploration” was off-limits in gender-affirming spaces.

As a long-time narrative therapist and someone who has lectured on family therapy at Boston University since 2015, I have every intention of taking this on– but not in this post.

In my opinion and without mincing words, Spiliadis took one of the most liberatory frameworks in all of contemporary psychotherapy and used it as a weapon. What he describes in his paper is leveraging his power in unacceptable ways to restructure a client’s self-knowledge to meet his own ends. While the paper draws on and describes essential concepts like the Brunerian “Landscape of Action” – he uses the language of Narrative practice as a trojan horse to practice what is clearly and unmistakably coercion.